Linguistics, in the simplest sense, is the study of languages. But what happens when the language itself has been lost to time, when there are no native speakers left, when there are scant records, if any, of its vocabulary and syntax? Herein lies the fascinating, intricate field of linguistic archaeology, the scientific study of ancient, often extinct languages. The challenge of resurrecting dead languages is not a mere academic exercise; it is a quest to revive a piece of human heritage that offers insight into how our ancestors communicated, thought, and lived.

Understanding Dead Languages

Before we delve into the resurrection process, we need to understand what is meant by a “dead” language. In linguistic terms, a dead language is one that no longer has any native speakers. The most well-known of these is probably Latin, once the lingua franca of the Roman Empire and now only read, not spoken conversationally.

However, being “dead” doesn’t mean a language is gone or irrelevant. Many dead languages influence modern tongues and contribute to our understanding of historical, cultural, and social contexts. For example, Latin is still widely used in law, science, and theology. The legacy of ancient Greek is evident in the arts and philosophy, while Sanskrit is revered as a sacred and literary language in South Asia.

A Glimpse into Linguistic Archaeology

Linguistic archaeology, often termed as “linguistic paleontology,” is a branch of historical linguistics. It is concerned with studying linguistic artifacts, such as inscriptions, manuscripts, or even oral traditions, and reconstructing ancient languages by using comparative, typological, and computational methodologies.

Linguistic archaeologists serve as detectives, decoding clues from the past and piecing together elements of lost languages. This intricate process of resurrection relies heavily on finding linguistic connections, shared roots, and borrowed words from neighboring languages or predecessor tongues.

The Process of Resurrection

Collection and Analysis

The resurrection of a dead language begins with gathering all available evidence about it. This can include ancient texts and inscriptions, related languages, historical records, and cultural contexts. The more information that can be gathered, the better the understanding of the language will be.

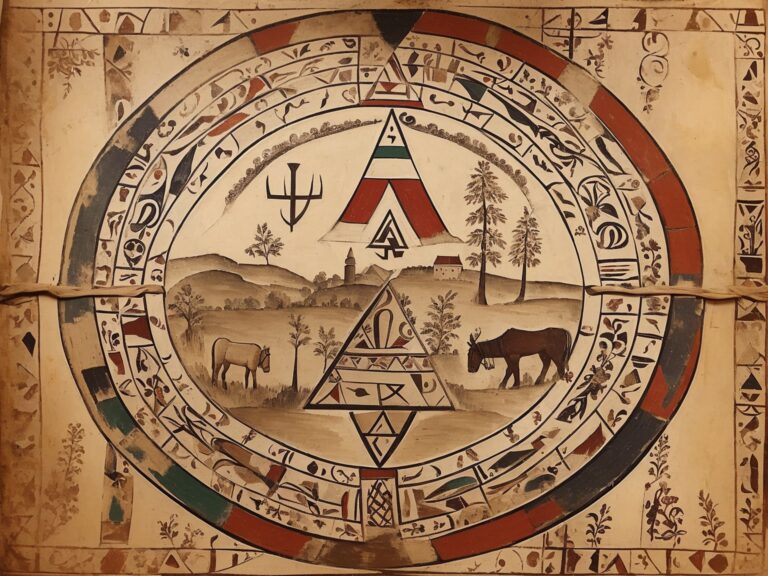

The deciphering of the Rosetta Stone, for example, was only possible because it had the same text written in three scripts – Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, Demotic script, and Ancient Greek. The ability to read Ancient Greek allowed for the understanding of the hieroglyphs, leading to a significant breakthrough in Egyptology.

Comparative Reconstruction

Next comes the application of the comparative method, a systematic procedure for reconstructing dead languages. This involves comparing words and grammatical structures across different languages, identifying similarities, and tracing these similarities back to a common ancestral language. This reconstructed “proto-language” then provides a basis for understanding its descendants.

Take, for instance, the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE), reconstructed using this method. PIE is the hypothetical common ancestor of the Indo-European languages, which include English, French, German, Russian, Greek, Hindi, and many others.

Computational Linguistics

In the digital era, computational linguistics has become a game-changer in linguistic archaeology. The application of artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms to vast linguistic datasets has accelerated the analysis of ancient languages. By automating the comparison of phonetic and grammatical patterns, it’s possible to identify linguistic connections faster and more accurately than ever before.

Revitalization

Revitalizing a dead language is the final and perhaps the most challenging part of the process. It requires creating a modernized version of the language that can be used for daily communication while remaining true to its historical roots.

A prime example is the revitalization of Hebrew. Once a liturgical language with no native speakers, it was systematically revived in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to become the spoken and written language of modern Israel.

Challenges and Ethical Considerations

The resurrection of dead languages is not without challenges and controversies. For one, there is the question of authenticity. How accurately can a language be reconstructed without native speakers?

There are also ethical issues to consider. In cases where a language died out due to colonization or oppression, the act of reviving it could be seen as cultural appropriation. It’s important that such endeavors are respectful of the communities to which these languages originally belonged.

Moreover, some argue that resources would be better spent on language preservation – saving endangered languages before they become extinct, rather than resurrecting dead ones.

The Importance of Resurrecting Dead Languages

Despite the challenges, the resurrection of dead languages is of immense value. It allows us to better understand the cultures and societies of the past, and it can help to restore cultural identity and heritage. Every language provides a unique perspective on the world, and by resurrecting a language, we gain another window into the human experience.

Resurrecting dead languages also enhances our understanding of language evolution and human migration patterns. It offers insights into how languages change over time and how linguistic similarities and differences arise.

Conclusion

In the grand scheme of human history, languages come and go, shifting, transforming, and sometimes disappearing altogether. But each one, whether still spoken or long dead, tells a story about those who used it to express their thoughts, dreams, and realities.

The field of linguistic archaeology, dedicated to unearthing and revitalizing these lost languages, offers us the chance to listen to these stories anew. It’s a journey that brings us closer to our collective past and enriches our understanding of the diverse tapestry of human expression. It is a testament to our relentless curiosity and our continuous quest to decipher our origins.