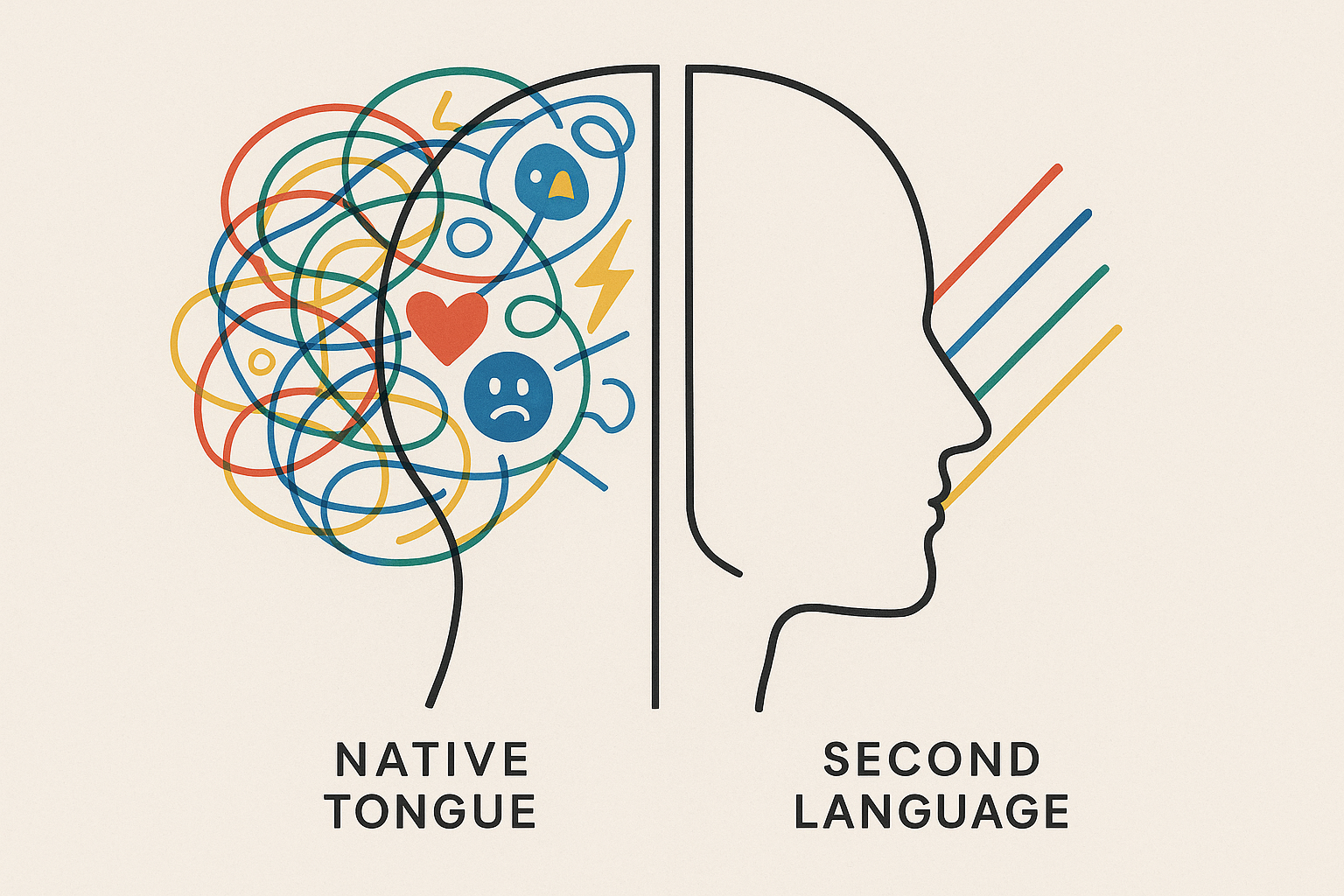

“Poetry,” the American poet Robert Frost famously quipped, “is what gets lost in translation.” It’s a wonderfully cynical and often accurate statement. How can a translator possibly carry the delicate architecture of a poem—its rhythm, rhyme, wordplay, and cultural echoes—across the treacherous sea from one language to another without it collapsing into a heap of mere words? The task seems impossible, a fool’s errand. And yet, we have magnificent translations of Homer, Rilke, Rumi, and Bashō that move us to tears, proving that while something may be “lost,” something profound can also be found, or perhaps more accurately, re-created.

Unlike prose, which is primarily concerned with conveying a narrative or an argument, poetry operates on multiple frequencies at once. It’s meaning, yes, but it’s also music, image, and feeling, all fused together by the specific sounds and structures of its original language. To translate a poem is not to be a stenographer, but an artist in your own right—a musician transcribing a symphony for a new instrument, or a painter reproducing a masterpiece in a different medium.

The Echo of Sound: Meter, Rhythm, and Rhyme

The most immediate challenge in poetic translation is sound. The sonic quality of a poem—its cadence, meter, and rhyme scheme—is not mere decoration; it’s an integral part of its emotional engine. Consider the steady, heartbeat-like rhythm of iambic pentameter in a Shakespearean sonnet, or the playful, sing-song quality of a limerick. This musicality shapes how we receive the poem’s meaning.

The problem is, languages have fundamentally different musical properties. English is a stress-timed language, where the rhythm is determined by the pattern of stressed syllables. In contrast, languages like Spanish or French are syllable-timed, where each syllable takes up roughly the same amount of time. A meter that sounds natural and powerful in one can feel forced and clunky in another.

Take the Japanese haiku, a form defined by its 5-7-5 structure. This count refers to on, or sound units, which are not exactly equivalent to English syllables. A direct, syllable-for-syllable translation of Matsuo Bashō’s famous poem often falls flat:

Furu ike ya

kawazu tobikomu

mizu no oto

A literal translation might be “Old pond / frog jumps in / water’s sound,” which captures the image but lacks poetry. Translating it as “An old silent pond / A frog jumps into the pond— / Splash! Silence again,” as translator Harry Behn does, sacrifices the strict syllable count to preserve the poem’s core emotional event: the piercing of silence. The translator had to choose: preserve the form or preserve the spirit? In most cases, spirit wins.

Rhyme presents a similar dilemma. Languages have different phonetic inventories and rhyming possibilities. Finding a perfect rhyming equivalent that also carries the same meaning is often impossible. The translator must decide whether to sacrifice the rhyme for literal accuracy or find a new rhyme that captures a similar feeling, even if it means altering the words slightly. The best translators often opt for the latter, finding clever “near rhymes” or creating a new sonic pattern that feels authentic to the target language.

A Metaphor in Another Tongue

Poetry thrives on figurative language—metaphors, similes, and idioms that create rich layers of meaning. But these devices are rarely universal. They are born from a specific culture’s experience, environment, and history.

A literal translation can often be confusing or downright comical. The English idiom “it’s raining cats and dogs” becomes absurd in most other languages. A Spanish translator would instead use está lloviendo a cántaros (“it’s raining by the pitcher-full”), swapping the bizarre image for one that conveys the same meaning of a heavy downpour. The goal is not to translate the *words* of the metaphor, but its *function*.

Sometimes, the challenge is deeper. A single word can contain a universe of cultural meaning. The German word Waldeinsamkeit describes the unique feeling of solitude and spiritual connection one feels when alone in a forest. A translator could write “forest loneliness,” but that phrase is sterile; it lacks the deep romantic and philosophical connotations the word holds for a German speaker. The translator must then make a difficult choice: use a less precise but more poetic phrase, keep the original term and explain it in a footnote, or try to weave the concept into the verse over several lines. Each choice alters the reader’s experience.

The Impossible Pun: When Words Play Double Games

If there is one feature of poetry that is truly “untranslatable,” it is the pun. Wordplay relies on the happy accident of a single word having multiple, often contradictory, meanings or sounding like another word. This is, by definition, language-specific.

Shakespeare is the undisputed master of the untranslatable pun. In Romeo and Juliet, a dying Mercutio, stabbed and bleeding, tells his friends:

“Ask for me to-morrow, and you shall find me a grave man.”

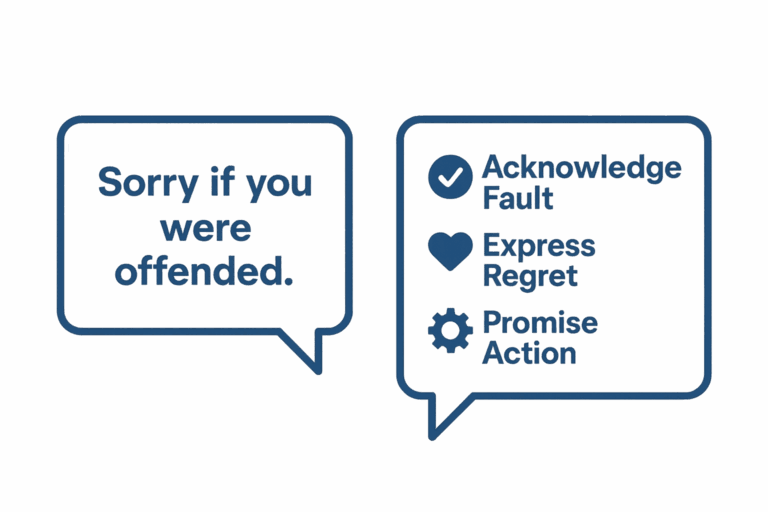

The genius lies in the double meaning of “grave”—both serious and in a burial plot. This grim, witty wordplay is impossible to replicate directly in another language. A translator is faced with an unenviable set of options:

- Translate one meaning: Simply translate “serious man,” losing the pun and much of Mercutio’s character.

- Explain it: Use a footnote to explain the pun, which rips the reader out of the moment and destroys the theatrical effect.

- Invent a new pun: This is the most creative and difficult path. The translator must find a different word in the target language that carries a similar double meaning appropriate to the context. It’s a moment where the translator must become a poet themselves.

The Ghost in the Machine: Cultural Resonance

Beyond individual words and phrases, poems are saturated with cultural resonance. They allude to myths, historical events, religious texts, and social norms that the original audience would understand instantly. This shared context is a silent partner in the poem’s meaning.

Translating Homer’s Odyssey, for instance, involves more than just finding the right words for ships and gods. When Homer describes the “rosy-fingered Dawn,” a modern English reader appreciates the beautiful image. But for the ancient Greek audience, those words instantly invoked Eos, the goddess of the dawn, with her entire mythological backstory. While the translator can convey the image, can they truly convey the full weight of that cultural shorthand? The resonance is inevitably different.

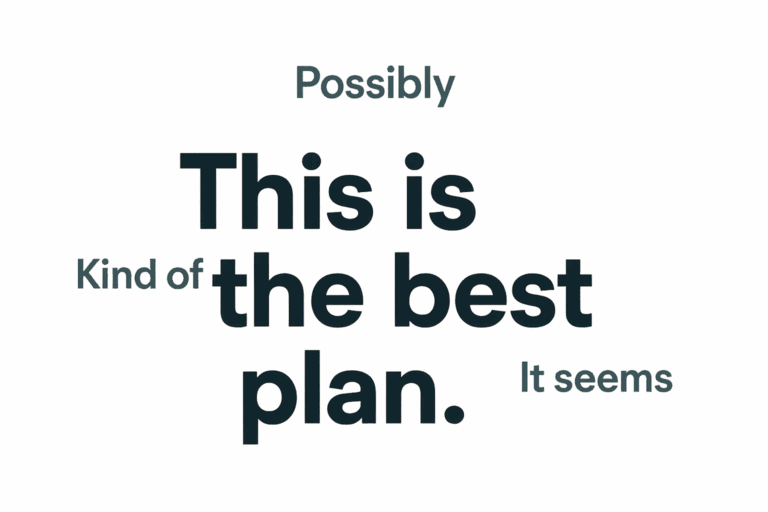

The translator must act as a cultural bridge, deciding how much context to embed within the poem itself and how much to leave for the reader to discover. They must create a new text that can stand on its own, offering its new audience an experience that is emotionally and intellectually parallel to the original, even if it’s not identical.

The Translator as Co-Creator

So, is poetry what gets lost in translation? Perhaps. But it is also what is reborn. The process is not one of mechanical substitution but of deep, empathetic interpretation and artistic recreation. The translator must dismantle the original poem down to its essential components—its sound, its imagery, its feeling, its ideas—and then rebuild it using the unique materials of a new language.

A great translation is not a shadow of the original; it is a new poem that sings in harmony with it. It allows a soul from one time and place to speak directly to a soul in another. The translator, far from being a traitor (as the Italian adage traduttore, traditore suggests), becomes a vital co-creator, giving the poem a new body, a new voice, and a new life.