It’s one of the most famous cautionary tales in marketing folklore: the story of the Chevrolet Nova in Latin America. As the legend goes, General Motors couldn’t figure out why their new car was failing to sell in Spanish-speaking countries, until they realized that “no va” translates literally to “it doesn’t go.” A car named “Doesn’t Go”—what could be worse?

The only problem? The story isn’t really true. The Chevy Nova actually sold reasonably well in markets like Venezuela and Mexico. In Spanish, the two words “no va” are distinct from the single brand name “Nova,” and consumers were perfectly capable of telling the difference. But while the tale may be an urban legend, its endurance speaks to a fundamental truth: in the high-stakes world of global branding, language is a minefield. A name that’s a stroke of genius in one country can be a career-ending blunder in another. This journey into brand name linguistics reveals how phonetics, cultural connotations, and even the basic building blocks of words can make or break a product on the world stage.

The Phonetic Pitfall: When It Just Sounds Wrong

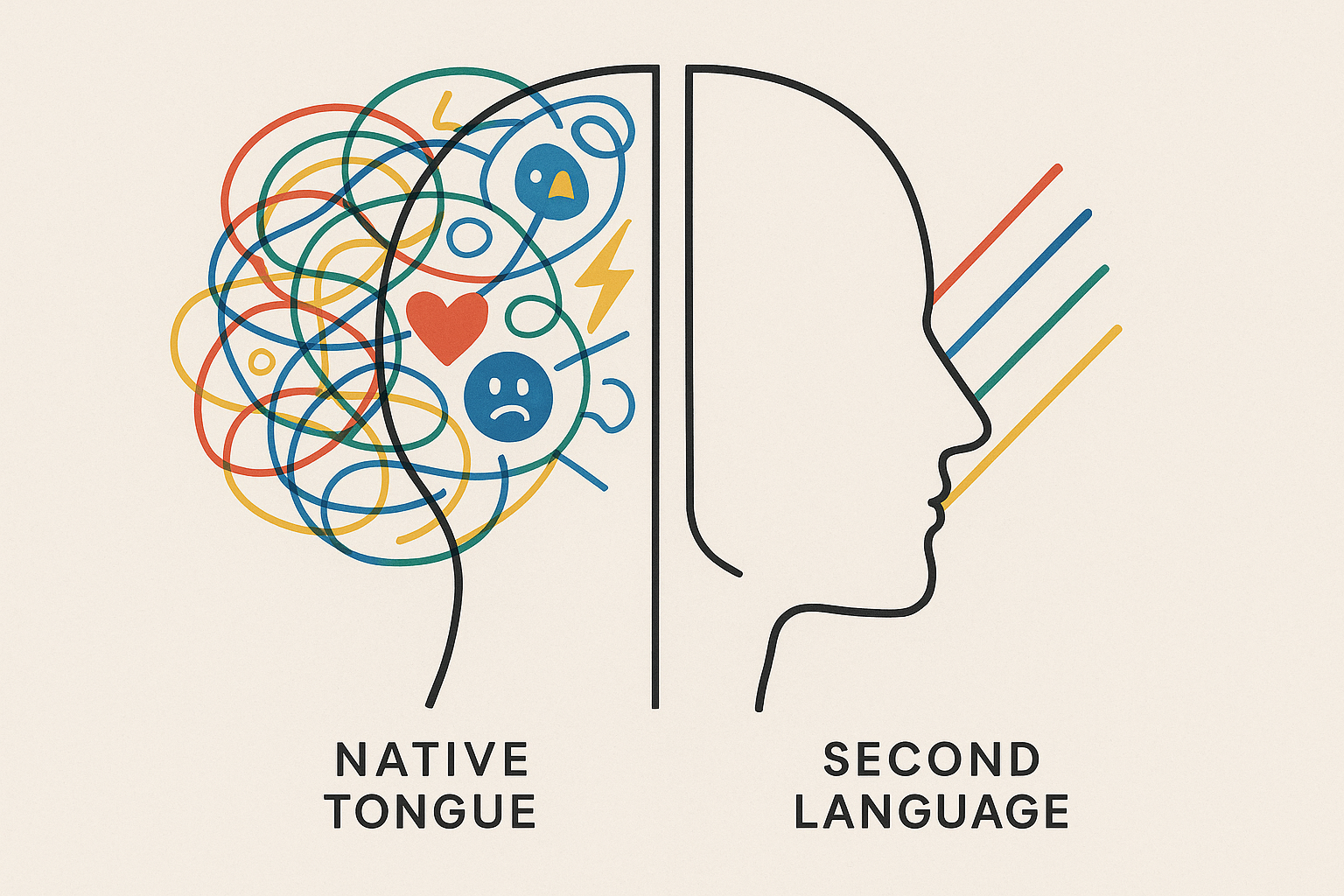

Before a customer even knows what a word means, they hear how it sounds. Phonetics—the study of speech sounds—is the first hurdle for any global brand. A name that rolls off the tongue in English can be a tongue-twister in Mandarin or a phonetic faux pas in French.

Consider the French soft drink brand “Pschitt.” In French, the name is a brilliant piece of onomatopoeia, perfectly evoking the fizzing sound of a freshly opened soda bottle. Export that name to English-speaking markets, however, and you’re left with a product that sounds uncomfortably close to… well, something else entirely. The name itself becomes a joke, completely overshadowing the product.

Sometimes the issue isn’t offensive, just difficult. When the Irish cream liqueur “Baileys” first launched in Germany, it faced an unexpected phonetic problem. The “ey” sound at the end doesn’t have a simple equivalent in German, leading to a variety of awkward pronunciations. While the brand ultimately succeeded, it’s a reminder that ease of pronunciation is a key component of memorability and adoption.

Brands that get this right often choose names with simple, open vowel sounds that are common across many languages. Think of names like Ikea or Coca-Cola—they are phonetically simple and adaptable, allowing them to be pronounced (with minor variations) by billions of people worldwide.

The Semantic Slip-Up: Lost in Translation

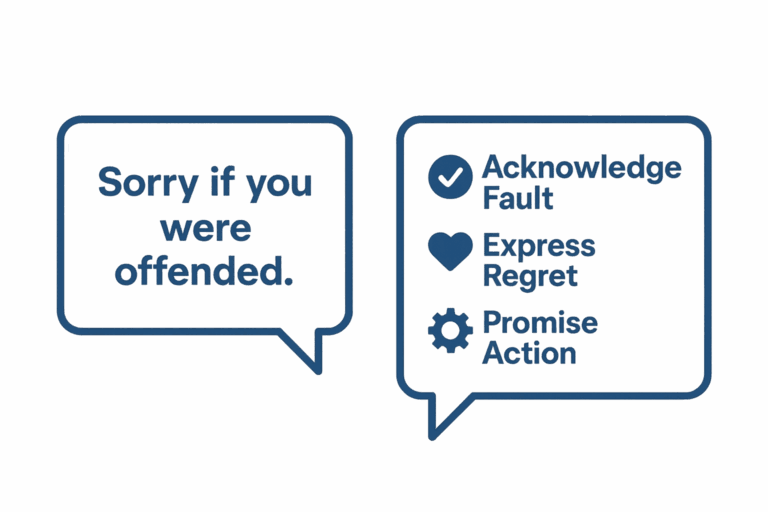

This is where we return to the ghost of the Chevy Nova. Semantics, or the meaning of words, is the most famous and often most hilarious area of branding blunders. While the Nova story is a myth, plenty of real-world examples prove the point.

- Ford Pinto: In the 1970s, Ford launched its subcompact car, the Pinto, in Brazil. They were met with deafening silence. It turned out that in Brazilian Portuguese, “pinto” is vulgar slang for small male genitalia. Ford quickly rebranded the car as the Corcel, which means “steed” or “stallion”—a much more fitting name for a car.

- Honda Fitta: Before it was known as the Fit in the US or the Jazz in Europe, Honda planned to call its new compact car the “Fitta.” A last-minute check revealed that in Swedish, Norwegian, and Danish, “fitta” is a crude and derogatory term for female genitalia. The name was wisely scrapped.

- Mercedes-Benz: When Mercedes entered the Chinese market, they initially used the brand name “Bensi.” Unfortunately, this translated to “rush to die.” They later changed it to the much more auspicious “Benchi” (奔馳), which means “dashing speed” or “to run quickly.”

However, navigating semantics can also be a path to genius. The most celebrated example is Coca-Cola in China. The company didn’t just find a name that sounded similar; they found one with a perfect meaning. The name 可口可乐 (Kěkǒu Kělè) is phonetically close to the original and translates to “tasty fun” or “to permit the mouth to be happy.” It’s a masterclass in not just avoiding a negative meaning, but creating a positive one.

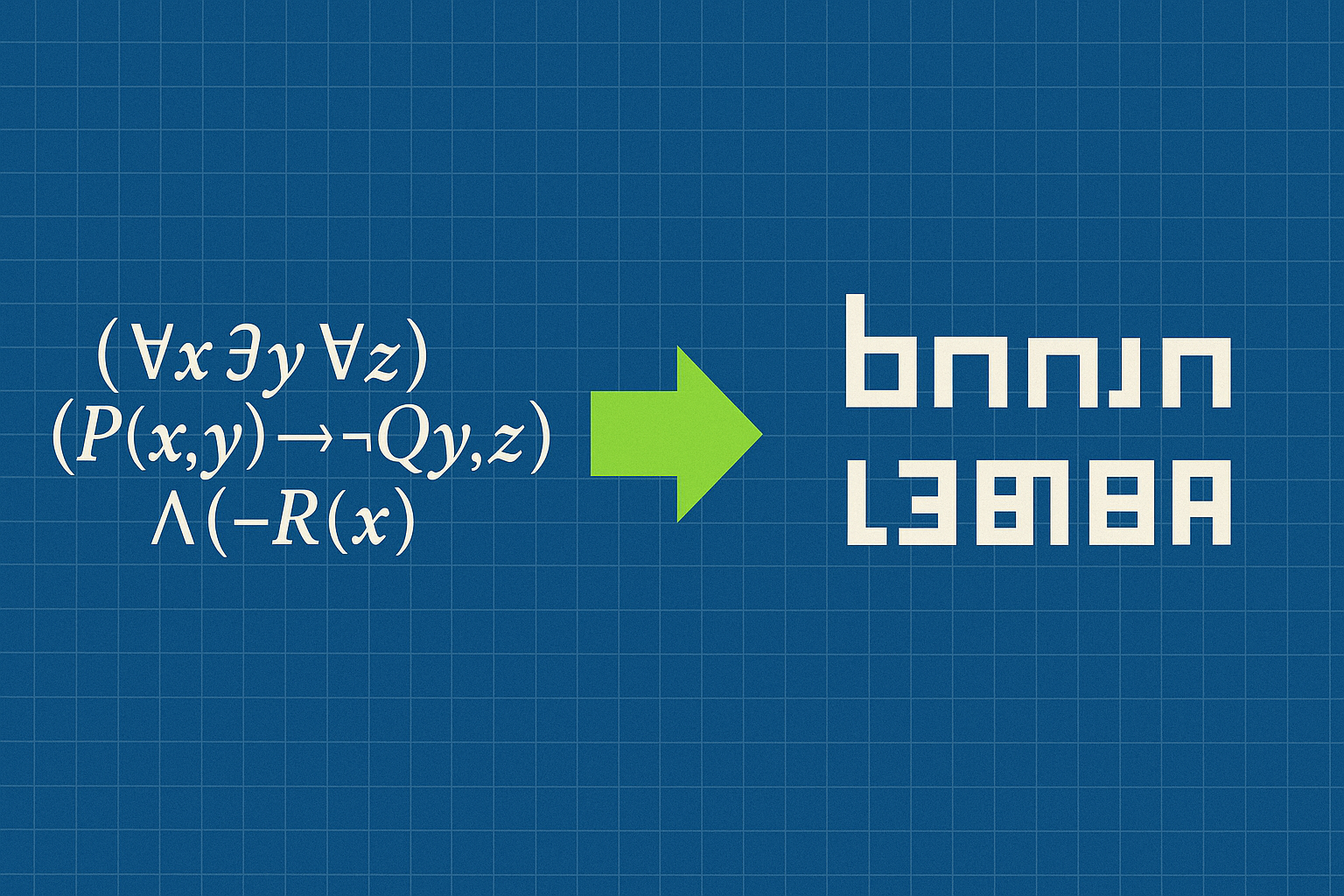

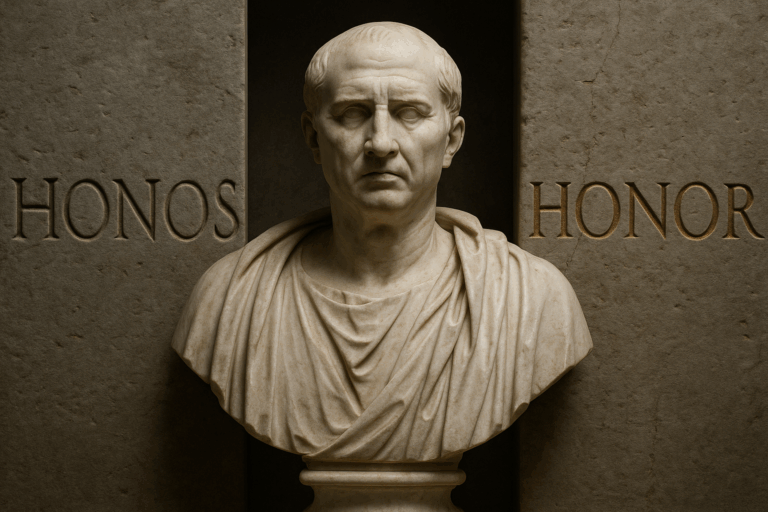

The Morphological Magic: Building Meaning from Scratch

Beyond sound and direct translation lies morphology—the study of how words are formed. This is the secret architecture of language, involving prefixes, suffixes, and roots that convey subconscious meaning. Many of the most successful global brands have names that are complete neologisms (invented words), but they are far from random.

These names are carefully constructed from morphemes that feel familiar and positive. Think of luxury and tech brands:

- Acura: This name was invented by a branding agency for Honda’s luxury line. It was built around the morpheme “Acu,” suggesting “accuracy” and “precision.” It sounds technical, sophisticated, and has no prior meaning in any language, making it a blank slate for the brand to define.

- Lexus: Similarly, Toyota’s luxury brand name suggests both “luxury” and the Latin word “lex,” meaning “law.” It evokes a sense of elegance, order, and high standards.

- Verizon: A portmanteau of the Latin word veritas (truth) and “horizon.” The name is meant to imply reliability and forward-thinking vision.

By building names from these powerful, often Latin-based morphemes, companies create words that feel substantial and meaningful even when they are entirely new. This strategy neatly sidesteps the phonetic and semantic traps of using existing words. It’s an attempt to create a truly universal language of branding, understood not through translation, but through a shared feeling and intuition about how words are built.

Speaking a Global Language

In our hyper-connected world, launching a product is almost always a global act. The days of a name existing in a single cultural bubble are over. As these examples show, brand name linguistics is not a trivial pursuit; it’s a critical business function that requires deep cultural and linguistic expertise.

Success requires more than just running a word through Google Translate. It demands a holistic understanding of how a name will be heard by a native speaker in Tokyo, how it will be read by a teenager in Berlin, and what hidden meanings it might carry for a family in Buenos Aires. The brands that thrive are those that realize they aren’t just selling a product—they are communicating an idea. And to do that successfully, you have to speak the language. All of them.