We all know the word crash. In a single syllable, it conjures the sound of a car collision or a plate shattering. We have moo for a cow, buzz for a bee, and thump for a heavy fall. This is onomatopoeia: words that imitate sounds. But what if a language had words that could imitate the sensation of smoothness, the sight of something sparkling, or the feeling of a heart pounding in your chest?

Welcome to the world of ideophones. Far more than just sound effects, these remarkable words are vivid sensory depictions that form a core part of communication in thousands of languages around the globe. They are the “adverbs of the senses,” and they reveal a profound connection between sound and meaning that often gets overlooked in English.

So, What Exactly Is an Ideophone?

Linguists define ideophones as “marked words that depict sensory imagery.” Let’s break that down:

- Depict Sensory Imagery: This is their core function. While an English adverb like “quickly” describes the speed of an action, an ideophone describes the quality or texture of it. It doesn’t just tell you something happened; it makes you see, hear, or feel it.

- Marked Words: Ideophones often stand out from the “normal” words in a sentence. They might have a unique sound structure (like repeating syllables), ignore typical grammar rules, or be delivered with a special intonation. They are linguistic highlights, designed to grab your attention.

The key difference from onomatopoeia is breadth. Onomatopoeia is limited to sound. Ideophones cover the entire sensory spectrum: sight, touch, taste, smell, and internal feelings like pain, excitement, or dizziness.

A World of Sensation: Ideophones in Action

To truly grasp the power of ideophones, we need to see them in their natural habitat. Languages in East Asia and across Africa are particularly rich in these expressive words.

Japanese: A Universe of Gitaigo

Japanese is famous for its extensive system of sensory words. It even has two distinct categories:

- Giongo (擬音語): This is standard onomatopoeia, for words imitating sounds, like wan-wan (a dog’s bark) or zaa-zaa (the sound of heavy rain).

- Gitaigo (擬態語): This is where it gets fascinating. These are ideophones that describe states, actions, and feelings.

You encounter gitaigo constantly in Japanese conversation, literature, and especially manga. They add a layer of texture that English adjectives struggle to match.

Consider these examples:

- キラキラ (kirakira): Describes the sight of something sparkling or glittering, like stars, jewels, or clean glass. To say something is kirakira isn’t just to say it’s “shiny”; it’s to evoke the specific visual action of twinkling light.

- サラサラ (sarasara): Evokes a sense of smoothness and dryness. It can describe silky hair, fine-grained sand, or the rustling sound of dry leaves. The single word bridges touch and sound.

- ドキドキ (dokidoki): The feeling of a heart beating rapidly from excitement, love, or fear. It’s the internal, physical sensation of your pulse, not just the abstract emotion.

- ニコニコ (nikoniko): The visual of a person smiling cheerfully. It’s not just a smile; it’s a beaming, happy, and often silent expression.

Notice the reduplication (repeating syllables). This is a common feature of ideophones worldwide, often used to suggest a repeated or continuous action.

Zulu: The Performative Power of *-thi*

In Southern Africa, Bantu languages like Zulu have thousands of ideophones that are central to everyday speech. They are not just descriptive flair; they are a fundamental grammatical class.

Zulu ideophones are often used with the verb -thi, which roughly means “to say” or “to do.” The structure is essentially “it went [ideophone],” creating a dramatic and performative effect.

- Nhló: The quality of intense greenness. You could say utshani buthi nhló, meaning “the grass is perfectly green.”

- Bhuqe: The sensation of lying down in exhaustion. Ngafika ekhaya ngathi bhuqe embhedeni translates to “I got home and went bhuqe on the bed,” vividly depicting the act of collapsing.

- Cwá: Total, piercing silence. Kwathi cwá means “It became utterly silent.”

- Thwa: A sudden flash of light, like lightning. The word itself feels sharp and quick.

In these languages, leaving out the ideophone would be like an artist choosing to draw in black and white when they have a full palette of colors available. It’s possible, but you lose an incredible amount of richness and detail.

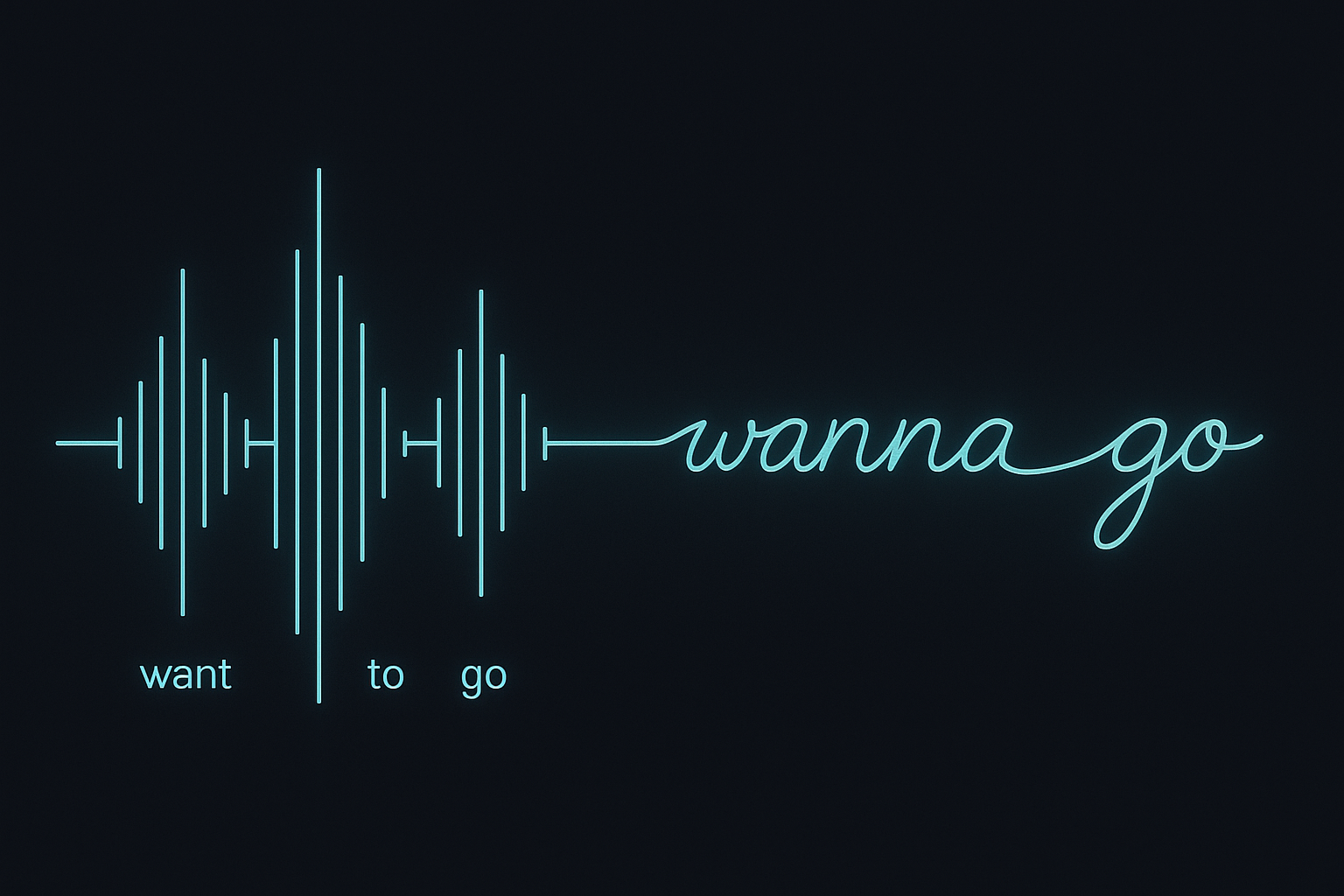

The Magic Behind the Words: Sound Symbolism

Why does kirakira *feel* like sparkling? Why does thwa *sound* like a flash? The answer lies in sound symbolism, the idea that the very sounds of a word can inherently carry meaning, independent of convention.

Even English has traces of this. Think of words starting with gl-: gleam, glisten, glitter, glow. They all relate to light. Or words with sl-: slip, slide, slick, slime. They share a sense of friction-free movement.

Ideophones are the ultimate champions of sound symbolism. Their phonetics are not arbitrary. High, sharp vowels like /i/ (as in “ee”) are often associated with small, quick, or sharp things. Low, round vowels like /o/ or /u/ are linked to large, slow, or heavy things. This is demonstrated by the famous “bouba/kiki effect,” where people across cultures overwhelmingly associate a spiky shape with the word “kiki” and a rounded shape with “bouba.”

Ideophones tap into this intuitive, almost universal human connection between sound and other sensory experiences to paint their vivid pictures.

Where Are the English Ideophones?

After reading about sarasara and bhuqe, English can feel a bit plain. While we have a few words that function like ideophones—pitter-patter, zigzag, helter-skelter, boing—they are rare. They are also often relegated to informal contexts, poetry, or children’s stories.

Why the difference? There’s no single reason, but a few factors are at play. English grammar has a fairly rigid system of adjectives and adverbs (often ending in -ly) for description. Ideophones, which act like verbs, adverbs, and adjectives all at once, don’t fit neatly into these categories. Furthermore, the history of written English has often prized a more formal, abstract style of description over the performative, embodied experience that ideophones provide.

The Language of Pure Sensation

Exploring ideophones is more than a linguistic curiosity. It’s a reminder that language is not just a tool for transmitting abstract information. It’s a way to share our direct, sensory experience of the world.

These “adverbs of the senses” show us that the sounds of our words can be as textured as silk, as bright as a flash of lightning, and as palpable as a beating heart. The next time you listen to a foreign language, keep an ear out. You might just hear a word that doesn’t just mean something—it *feels* like something.