Take a moment to say a few words out loud. “Hello.” “How are you?” “Linguistics is fascinating.” The ease with which you produced that complex stream of sounds is a uniquely human miracle, one we perform so effortlessly we rarely give it a second thought. But this ability hinges on a strange, and frankly, dangerous, quirk of our anatomy: a larynx that has dropped low in our throat. This is the story of the descent of the larynx—an evolutionary gamble that traded safety for the symphony of human speech.

What’s a Larynx, and Why Does its Position Matter?

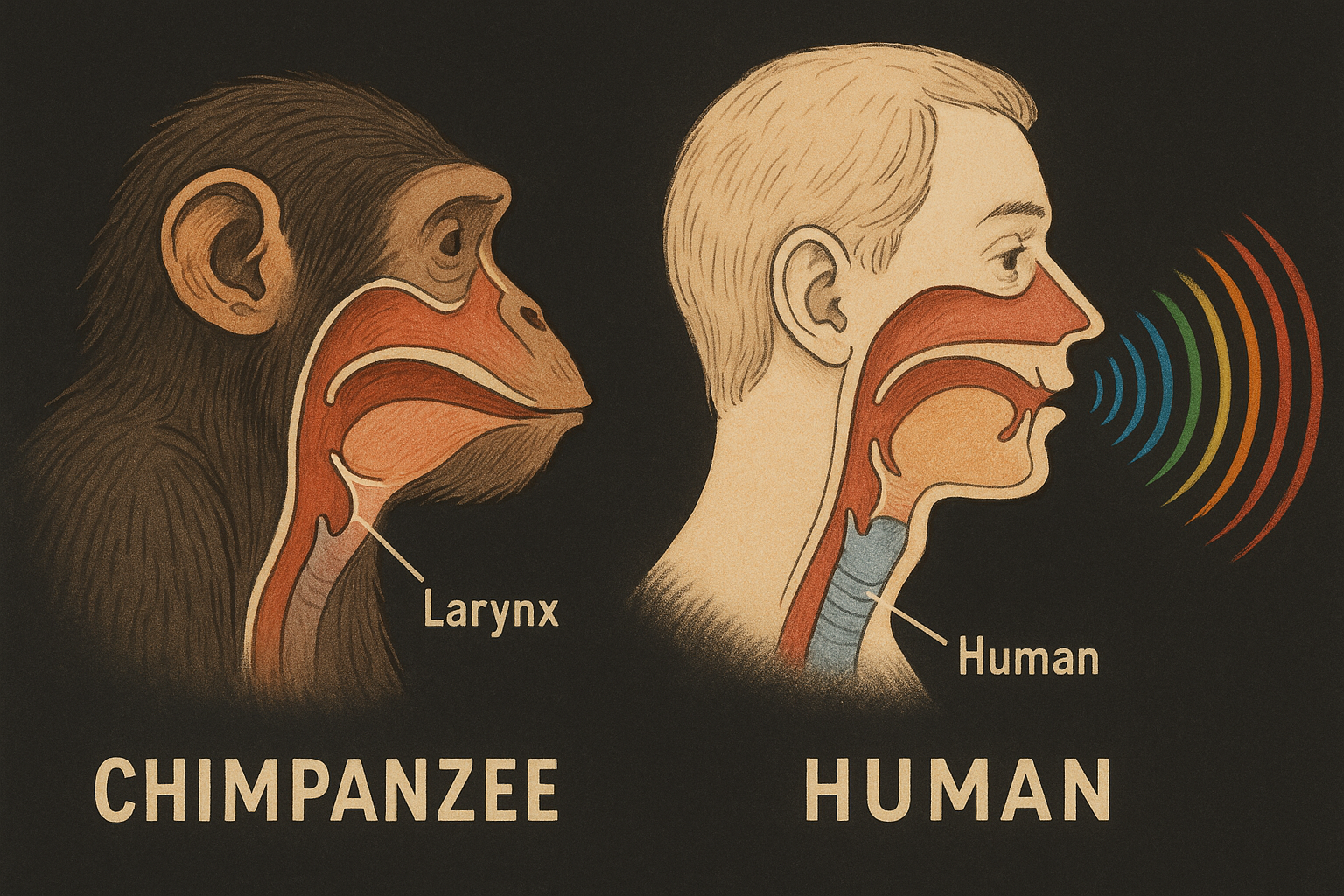

The larynx, or voice box, is a structure of cartilage and muscle at the top of your windpipe (trachea). It houses your vocal cords, which vibrate to produce the raw sound of your voice. In most mammals, including our primate cousins like chimpanzees and even human infants, the larynx sits high up in the neck. This high position allows the epiglottis—a flap of cartilage—to interlock with the soft palate, effectively creating two separate pipes: one for air (from the nose to the lungs) and one for food (from the mouth to the esophagus).

This is an ingenious design. It allows a baby, a cat, or a chimp to breathe and swallow at almost the same time without much risk of food “going down the wrong pipe.”

But in adult humans, something dramatic happens. Around the age of two, our larynx begins a slow descent, finally settling much lower in the throat. This descent completely reconfigures our vocal tract. The two separate, safe pipes are gone. Instead, the pharynx—the cavity behind the nose and mouth—becomes a shared passageway for both air and food. This anatomical crossroads is precisely why we are so uniquely susceptible to choking.

The Biomechanical Trade-Off: Crafting a Vocal Instrument

So, why would evolution favour a feature that puts us at a daily risk of a life-threatening accident? The answer lies in the incredible acoustic versatility it provides.

The descent of the larynx creates a large, L-shaped resonating chamber above the vocal cords, consisting of two main parts: the vertical pharynx and the horizontal oral cavity (your mouth). Think of it like the body of a violin or a guitar. The raw sound produced by the vibrating vocal cords is a simple buzz. It’s the shape and size of this two-part chamber that filters and amplifies that buzz into the rich and distinct sounds of speech.

By changing the shape of this chamber with our tongue, lips, and jaw, we can dramatically alter the sound’s resonant frequencies, known as formants. It is the precise manipulation of these formants that allows us to produce the full range of human vowel sounds. The “corner vowels” that are universal to almost all human languages—[i] (as in “beet”), [a] (as in “father”), and [u] (as in “boot”)—are only possible because we can create extreme configurations in our L-shaped vocal tract. An ape, with its high larynx and smaller pharynx, simply doesn’t have the anatomical hardware to produce this acoustic range.

- To make an [i] sound: We raise the front of our tongue high in the mouth, creating a large pharyngeal cavity and a small oral cavity.

- To make an [a] sound: We lower our tongue and jaw, creating a relatively narrow pharyngeal cavity and a large oral cavity.

- To make an [u] sound: We raise the back of our tongue, creating a large oral cavity and rounding our lips.

This acoustic flexibility is the foundation of the phonemic diversity we see in the world’s 7,000+ languages.

Sifting Through Fossils: The Hunt for the First Speakers

Pinpointing when this crucial descent occurred in our evolutionary history is a major challenge for paleoanthropologists. The larynx is made of cartilage, which doesn’t fossilize, so scientists have to rely on indirect clues from the skeletons of our ancestors.

The most debated piece of evidence is the basicranial flexion—the angle of the base of the skull. In modern humans, the skull base is highly flexed (arched), which is thought to accommodate our low-lying larynx. In apes, it’s much flatter. By examining the skulls of extinct hominins, we can look for signs of this flexion.

- Australopithecines (like “Lucy”): Their skull bases were flat, much like a chimpanzee’s, suggesting a high larynx and a limited vocal range.

- Homo erectus: Their skulls show a degree of flexion somewhere between that of apes and modern humans, suggesting their larynx may have begun its descent, granting them a wider vocal range than their predecessors, but not yet the full modern human capacity.

- Neanderthals: This is where things get really interesting. For a long time, it was believed Neanderthals had an ape-like vocal tract. However, the discovery of a Neanderthal hyoid bone—a small, U-shaped bone that supports the larynx—at the Kebara Cave in Israel changed everything. The Kebara hyoid is virtually identical to a modern human’s, suggesting it anchored a larynx that was positioned and capable of the same movements as our own. While their skull base was less flexed than ours, recent biomechanical models suggest they could have produced a range of sounds comparable to modern humans. The debate is far from over, but it’s clear they were not just grunting cavemen.

More Than Just a Voice Box

Of course, a descended larynx is only part of the puzzle. Having a finely tuned instrument is useless without a virtuoso to play it. The evolution of speech also required massive changes in the brain.

The development of key brain regions like Broca’s area (involved in speech production) and Wernicke’s area (involved in language comprehension) was essential. Furthermore, the incredible neural circuitry required for the fine motor control of our tongue, lips, diaphragm, and vocal cords cannot be overstated. Speech is a “full-body” activity, a complex dance between anatomy and neurology.

Ultimately, the descent of the larynx stands as a testament to the strange and wonderful paths of evolution. It was a high-stakes gamble—a compromise that traded primal safety for the power of complex communication. Every conversation we have, every story we tell, and every song we sing is made possible by this quirky, dangerous, and profoundly human shift in our anatomy.