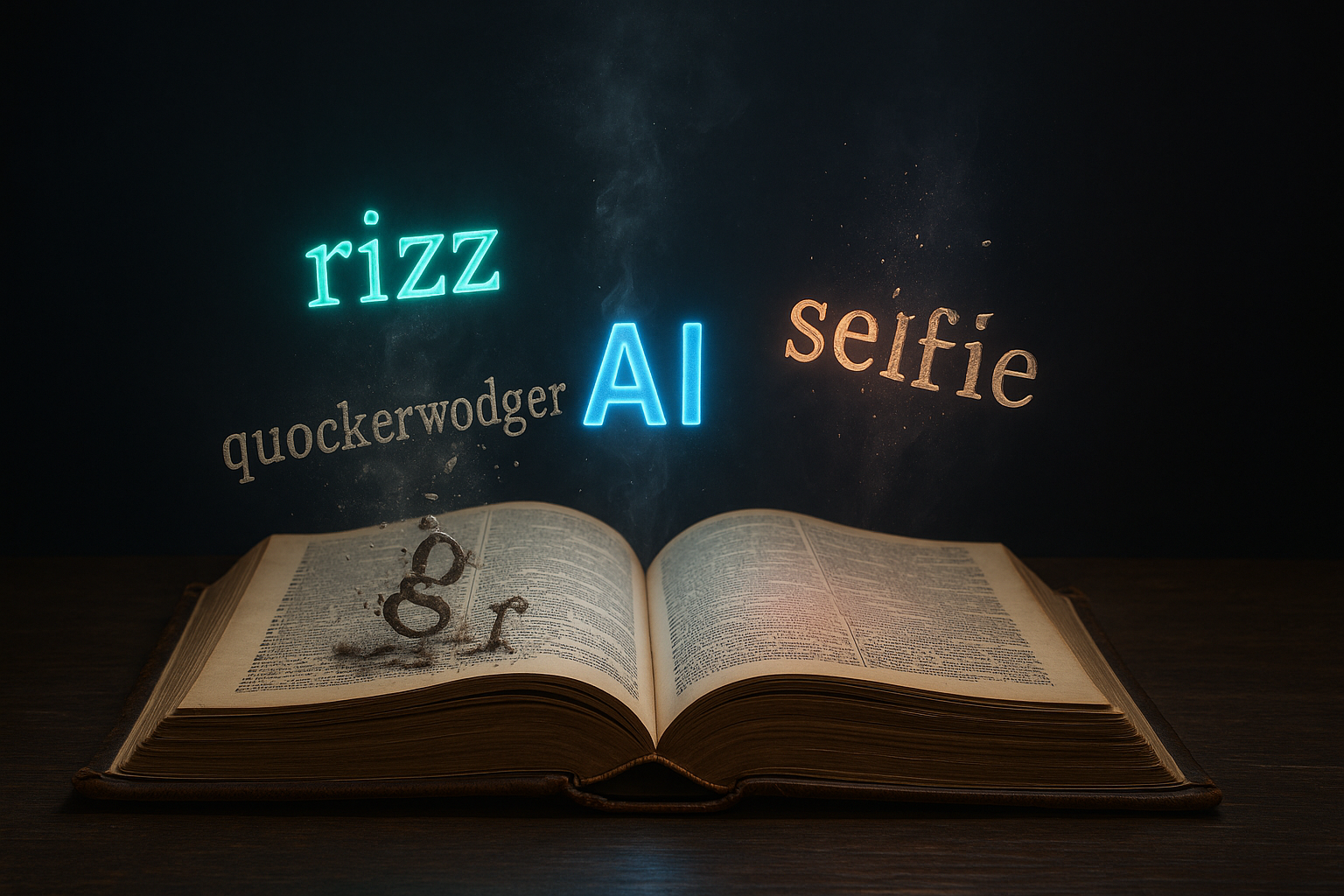

Every year, a fresh batch of words storms the gates of the English language. Terms like “rizz,” “doomscrolling,” and “prompt” (in its new AI sense) transition from niche slang to headlines, eventually earning a coveted spot in the dictionary. At the same time, other words wither on the vine. When was the last time you heard someone use “brabble” (to quarrel noisily) or “snollygoster” (a shrewd, unprincipled person) in casual conversation?

This constant churn raises a fascinating question: Who decides? Is there a shadowy council of etymologists in a smoke-filled room, passing judgment on our vocabulary? The reality is less dramatic but far more interesting. The life and death of words aren’t decreed by a select few; they are determined by a rigorous, data-driven process managed by lexicographers—the cartographers of our language.

They don’t decide who lives or dies. We do. The dictionary is just the coroner who records the time of death.

The Birth of a Word: Earning a Spot in the Dictionary

A word doesn’t become “real” the moment it appears in the dictionary. It becomes real the moment people start using it in a meaningful, consistent way. Lexicographers are linguistic detectives, hunting for evidence that a new word, or neologism, has achieved critical mass. To be considered for inclusion, a word must meet several key criteria:

- Widespread Use: It isn’t enough for a word to be popular within your friend group or a single online community. Lexicographers need to see the word used across a wide range of sources—in newspapers, books, magazines, academic journals, blogs, and even transcribed media. The more varied the sources, the stronger the case.

- Sustained Use: Language is full of fads. A word that’s a viral sensation one week can be forgotten the next. To avoid cluttering the dictionary with fleeting slang, editors look for staying power. Has the word been in use for a considerable amount of time (often a few years)? Does it look like it’s here to stay? “Doomscrolling,” born from the anxieties of 2020, has demonstrated this kind of longevity.

- Meaningful Use: The word must have a clear, distinct meaning that is broadly understood. If people are using a word in wildly different ways with no consensus, it’s not ready for an entry.

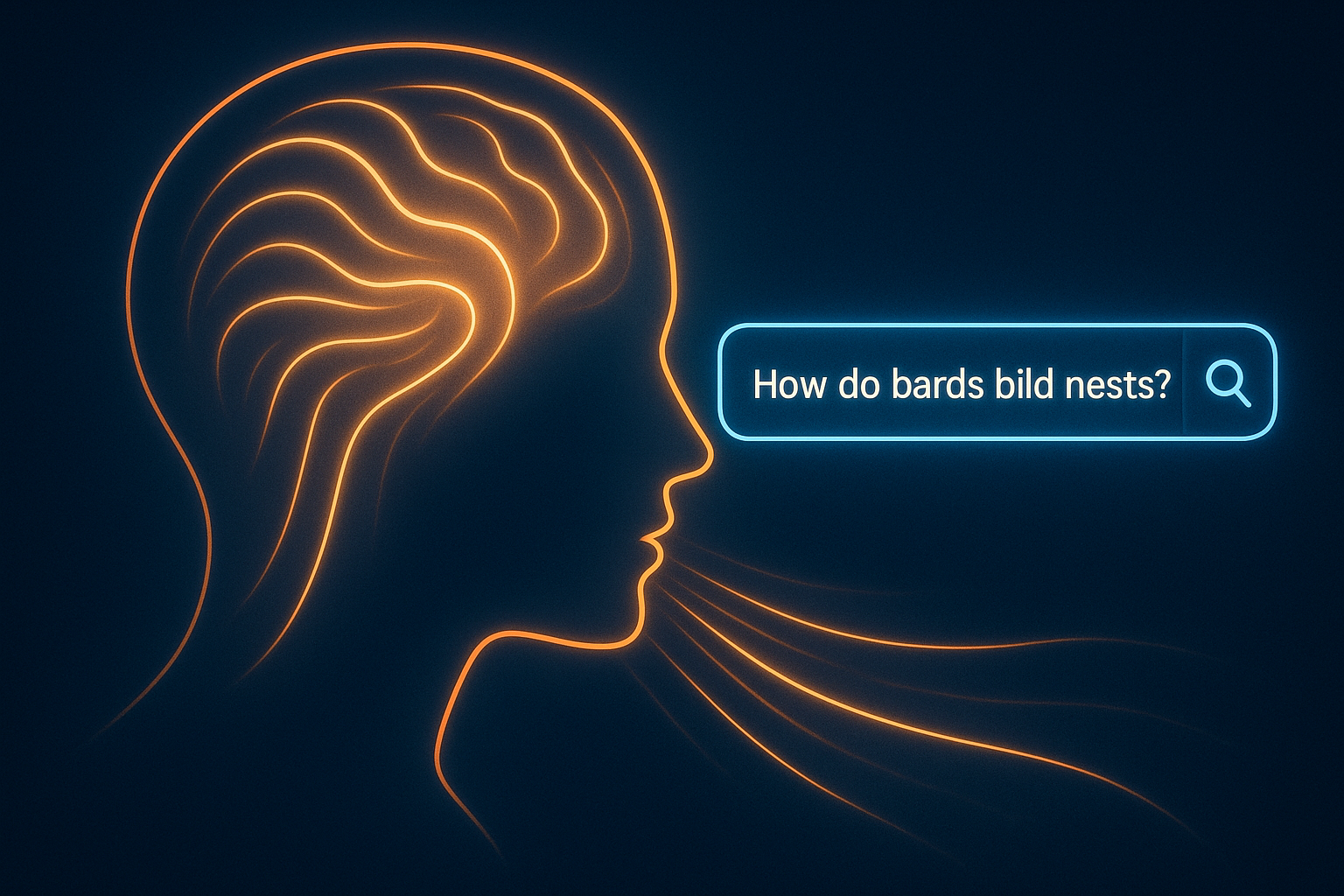

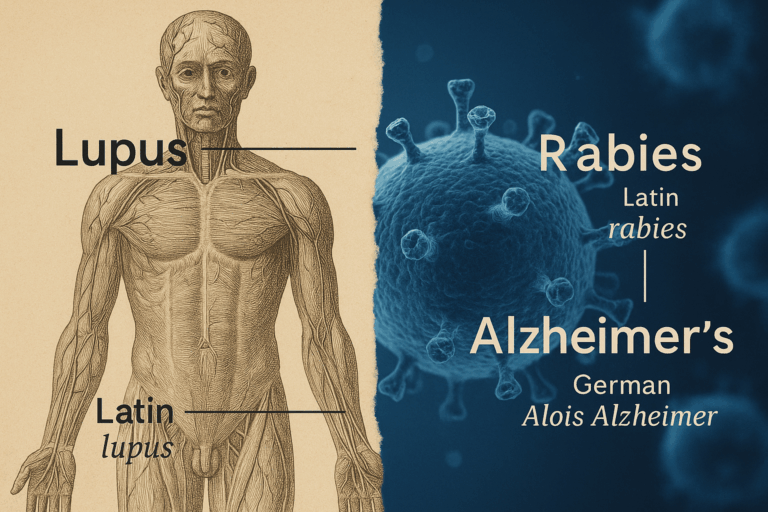

How do they track all this? Their primary tool is the corpus (Latin for “body”). A corpus is a massive, ever-growing, searchable database containing billions of words from countless texts. The Oxford English Corpus, for example, contains over 20 billion words from sources across the English-speaking world. By querying the corpus, lexicographers can see, in real-time, how often a word like “rizz” is appearing, who is using it, and in what context. When the data shows a word has met the criteria, its file is flagged, and the process of drafting a definition begins.

The Grey Area: Not Quite Dead, Just… Resting

Just as words are born, they also fade. But word death is rarely an abrupt event. Dictionaries don’t typically just delete words, especially historical dictionaries like the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), which aim to be a complete record of the language. Instead, they act as linguistic curators, applying labels to indicate a word’s current status.

You’ll often see two key labels:

- Archaic: These are the antiques of the language. An archaic word is one that is no longer in common use but may still be recognized, particularly from historical texts, poetry, or legal jargon. Words like “hark,” “whence,” and “perchance” fit this category. You wouldn’t use them to order a coffee, but you understand them when you read Shakespeare. They are part of our cultural heritage, preserved in the dictionary like artifacts in a museum.

- Obsolete: This is the official death warrant. An obsolete word has completely fallen out of use. The evidence for its active use has dried up, often for a century or more. Unlike an archaic word, most native speakers would not recognize it at all. Ever heard of “quagswag” (the act of shaking to and fro) or “latibulate” (to hide in a corner)? Probably not. They are the ghosts of the lexicon, their entries a historical record of a linguistic path no longer traveled.

Signing the Death Warrant: How a Word Dies

The process for labeling a word as archaic or obsolete is the mirror image of inclusion: it’s all about the lack of evidence. Using the same powerful corpora, lexicographers can see which words are disappearing.

If searches for a word yield fewer and fewer results from contemporary sources, and the only hits are from quotes of much older texts, its health is considered to be failing. The decline is tracked over decades. If it vanishes from living, breathing language, it is eventually marked as obsolete.

Why do words die in the first place? Several factors can contribute to a word’s demise:

- Technological and Social Change: When the object or concept a word describes disappears, the word often follows. Words like “haberdasher,” “cassette,” and “switchboard operator” have faded because the worlds they described have changed.

- Synonym Takeover: Language abhors a vacuum, but it also dislikes redundancy. Often, a word falls out of use simply because a competing synonym becomes more popular, fashionable, or precise. In American English, “airplane” largely vanquished its older cousin, “aeroplane.”

- Phonetic Awkwardness or Unfashionable Sounds: Sometimes, words just sound clunky to the modern ear. While harder to prove, it’s a contributing factor. A word that is difficult to say or sounds comical may be less likely to survive.

The Dictionary’s True Role: A Mirror, Not a Hammer

This brings us to the most crucial point about dictionaries. For centuries, people have viewed them as prescriptive authorities—rule books that dictate what is “correct” or “proper” English. But modern lexicographers see their role as descriptive.

A dictionary isn’t a hammer to beat the language into a specific shape. It’s a mirror held up to reflect the language as it is actually used by its speakers. It doesn’t make “rizz” a real word; it acknowledges that millions of people have already done so through their collective use. It doesn’t kill the word “brabble”; it simply notes that people have stopped saying it.

This is why lexicographers add slang, jargon, and even informal spellings. Their job is not to judge but to record. They are charting the dynamic, messy, beautiful evolution of human communication.

So the next time you hear a new word and wonder if it’s “real,” remember that you are part of the answer. Language isn’t owned by editors or academics. It’s a vast, democratic ecosystem, and every time you speak, write, or text, you cast a vote. You are a participant in the epic story of how words live and die.